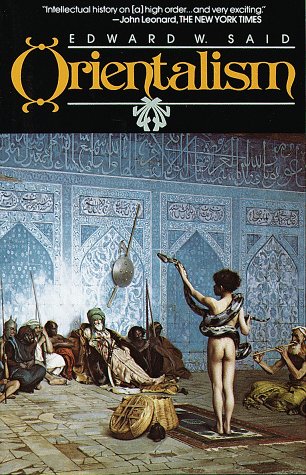

The Cover of Edward Said’s Orientalism

Post-Orientalism: Knowledge and Power in Time of Terror is a sustained record of Hamid Dabashi’s reflections over many years on the question of authority and the power to represent. Who gets to represent whom and by what authority? When initiated in the most powerful military machinery in human history, the United States of America, already deeply engaged in Afghanistan and Iraq, such militant acts of representation speak voluminously of a far more deeply rooted claim to normative and moral agency, a phenomenon that will have to be unearthed and examined. In his groundbreaking book, “Orientalism”, Edward Said traced the origin of this power of representation and the normative agency that it entails to the colonial hubris that carried a militant band of mercenary merchants, military officers, Christian missionaries, and European Orientalists around the globe, which enabled them to write and represent the people they thus sought to rule. The insights of Edward Said in “Orientalism” went a long way in explaining conditions of domination and representation from the classical colonial period in the 18th and 19th century to the time that he wrote his landmark study in the mid 1970’s. Though many of his insights still remain valid, Said’s observations need to be updated and mapped out to the events that led to the post-9/11 syndrome. Dabashi’s book is not as much a critique of colonial representation as it is of the manners and modes of fighting back and resisting it. This is not to question the significance of Orientalism and its principal concern with the colonial acts of representation, but to provide a different angle on Said’s entire oeuvre, an angle that argues for the primacy of the question of postcolonial agency. In Dabashi’s tireless attempt to reach for a mode of knowledge production at once beyond the legitimate questions raised about the sovereign subject and yet politically poignant and powerful, postcolonial agency is central. Dabashi’s contention is that the figure of an exilic intellectual is ultimately the paramount site for the cultivation of normative and moral agency with a sense of worldly presence. For Dabashi the figure of the exilic intellectual is paramount to produce counter-knowledge production in a time of terror.

Praise for Post-Orientalism: Knowledge and Power in Time of Terror

In this stirring book, Hamid Dabashi defines the strength of “defiant subjects” by advancing one of the most committed readings of Edward Said’s life and works; calling for an unequivocal affirmation of exile, for “being at home in not being at home;” drawing a moving, critical portrait of Ignaz Goldziher; delivering a sparring homage to Gayatri Spivak in the name of “the polivocality of dissent;” elaborating “the creative constitution of a historical agency beyond the pale of colonial modernity” in the cinema of Mohsen Makhmalbaf; reclaiming transformative border-crossing, the “revolutionary hybridity” at work in the militant life of Che Guevara, Franz Fanon, Malcolm X, and Ali Shari’ati; and engaging the sorry state of knowledge production in the United States. Post-Orientalism is an impressive display of synthetic erudition, which attends to alternative and essential, but not essentialized, conversations with “changed interlocutors.” There is a war on, Dabashi tells us, but no sides to speak of. And so he shows himself, ever more compellingly and perhaps above all, as a “confessor of Oneness,” indeed, a universalist and “amphibian” intellectual.

— Gil Anidjar, author of The Jew, the Arab: A History of the Enemy

In this fascinating and prodigious work, Hamid Dabashi offers a compelling analysis of the varied phases and modes of Orientalism and persuasively demonstrates the mutations in the evolving modes of knowledge production about Islam and the Middle East. But Post-Orientalism is much more than that. It successfully holds the difficult balance between theoretical sophistication and political engagement in its examination of the imaginary created by the specific manners of knowledge production in a world dominated by the United States, what he calls “an empire without hegemony.” Dabashi’s admirably well argued suggestion to decolonize our analytical apparatus and the need to attend to local geographies so as to develop cross-cultural conversations is substantiated by his critical but appreciative engagement with Edward Said’s, Gayatri Spivak’s and Ranajit Guha’s (and many others’) ideas and thus forges new avenues of research in postcolonial studies. He develops a stunning criticism of the nature of the symbolic imperialism exercised through the ideologies developed by figures such as Samuel Huntington, Francis Fukuyama, and Bernard Lewis. It is a conceptually and intellectually elegant, subtle and politically trenchant book and as such, it will interest everyone concerned with contemporary processes of global politics in a wide range of fields.

— Meyda Ye?eno?lu, author of Colonial Fantasies: Towards a Feminist Reading of Orientalism

Columbia University

Columbia University Aljazeera

Aljazeera Middle East Eye

Middle East Eye Springer Palgrave

Springer Palgrave