Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s “Kandahar” (2001)

Paramount in Makhmalbaf’s “Kandahar” (2001) is the presence of a testimony as to how a work of art transcends reality by teasing out its emancipatory forces — particularly in a colonial context where historical agency is to be articulated against an Enlightenment Modernity that has categorically denied it, and in fact made itself possible by doing so. More than in and of itself, Iranian cinema can be seen as a set of creative tropes of imaginative explosions emerging out of critical circumstances, where artists have been able to re-subject the categorically de-subjected in and through a colonially militated modernity. In trying to see how they could wrest their conception of the beautiful from rather bestial circumstances, one can detect a kind of Manichean cosmogony at work where artists seek to rescue the light of subjective emancipation from the very cruel heart of colonial darkness they have inherited. Under these circumstances, art emerges as the wresting of the otherwise of reality out of reality, not phantasmagorically hallucinating an outlandish ideal against the brutality of the real, but in fact acknowledging and even celebrating the real by teasing out its hidden and concealed otherwise. The global appeal of Iranian cinema in general, one might argue, is precisely because of the global disposition of the bondage (denial of agency) from which it seeks to emancipate a nation.

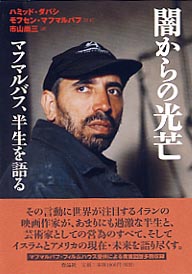

(From Hamid Dabashi’s essay “The Beauty of the Beast: From Cannes to Kandahar”)

Columbia University

Columbia University Aljazeera

Aljazeera Middle East Eye

Middle East Eye Springer Palgrave

Springer Palgrave