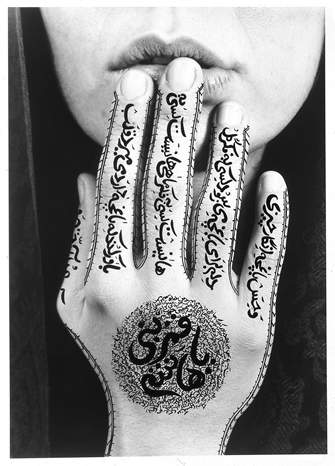

A work by Shirin Neshat

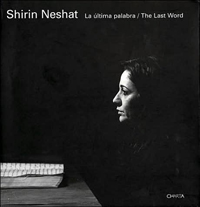

It is almost a decade since I wrote my very first essay on Shirin Neshat. Quite by serendipity, I had just seen a collection of her photographs in Venice Biennale in August 1995, where I happened to be and where I accidentally walked into a room in one of the Biennale venues and saw her pictures hanging on the wall next to a window overlooking one of the main canals. Soon after that, in May 1996, I run into Shirin Neshat herself (not knowing who she was) in the lobby of Walter Reade Theater at the Lincoln Center in New York during a major retrospective of Abbas Kiarostami that Richard Peña had organized. Here she was—with a huge portfolio of her work, almost as tall as her own height, showing her work to a friend when I accidentally saw her and her pictures and was quite surprised to discover that these were the pictures I had seen the year before in Venice. We soon stroke up a conversation, and after that an enduring friendship ensued. Soon after that encounter, I wrote my first essay on Shirin Neshat’s work, “The Gun and the Gaze,” for the first volume of her selected photographs, Women of Allah (1997).

The 46th Venice Biennale (1995), in which I saw Shirin Neshat’s work for the first time, was the first major group exhibition of her work. Soon after that other major exhibitions, both solo and in group, followed—chief among them the 10th Biennale of Sydney (1996), Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art (1997), the 5th International Istanbul Biennale (1997), the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale (1997), Tate Gallery of Modern Art (1998), the Art Institute of Chicago (1999), the 48th Venice Biennale (1999), Kunsthalle Wien (2000), the 3rd Kwangju Biennale (2000), Whitney Biennale, Whitney Museum of American Art (2000), Kanazawa Citizen’s Art Center (2001), Hamburger Kunsthalle (2001), Valencia Biennial (2001), Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea (2002), Documenta 11 (2002), and Sanctuary, Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art (2003). The span of time between her first and most recent work, between 1995 and 2005, covers a decade of the most radical and drastic events of our current history. Art has always had a specific social setting. But specific social settings have been scarcely so global in their consequences.

(From Hamid Dabashi’s “Shirin Neshat: Transcending the Boundaries of an Imaginative Geography”)

Columbia University

Columbia University Aljazeera

Aljazeera Middle East Eye

Middle East Eye Springer Palgrave

Springer Palgrave