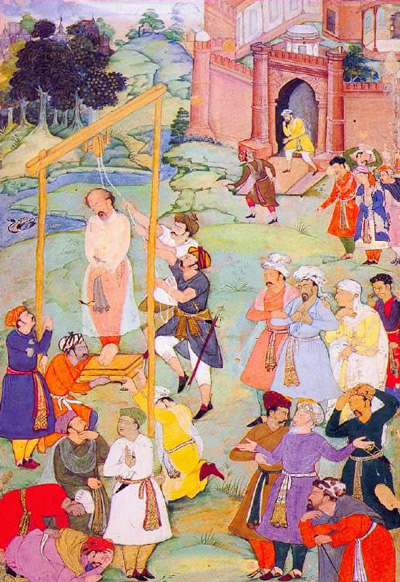

The Public Execution of Ayn al-Qudat in a Medieval Illustrated Manuscript

My main purpose in writing this book is to provide an intellectual portrait of Ayn al-Qudat al-Hamadhani (49211098-525/1131), one of the most remarkable figures in medieval Persian intellectual history. Although most of his writings in Persian and Arabic have been available in critical editions, there is no single volume that provides a concise statement about his life, thought, social and intellectual environment, and singular significance in Islamic and Iranian intellectual history.

Despite the fact that Ayn al-Qudat’s highly productive life and his unusually creative imagination were brought to an abrupt end when he was brutally executed at the age of thirty-three in his native Hamadhan, he has left us a remarkable body of work which provides an immediate access to the radical range of his ideas. Ayn al-Qudat was the recipient of a rich and diversified literary culture in which the combined yet contradictory forces of the sacred and the aesthetic imagination had played defining roles. By the late fifth/eleventh century, what today we call “Islamic” civilization had attained some of its more enduring achievements. An elaborate system of jurisprudence, a sustained body of speculative theology, monumental elaborations of the Aristotelian-Avicennian philosophy, and an ecstatically self-conscious narrative of what has been termed “Islamic Mysticism” (Sufism) were among the dominant intellectual domains of Ayn al-Qudat’s time. Beyond these quintessentially theocentric discourses, there was an immensely developed institution of humanism (or adab) to which Ayn al- Qudat had equal access and attraction. Locating Ayn al-Qudat in the universe of his received intellectual history provides a necessary back- ground against which his own unprecedented achievements may be assayed.

My reasons for writing this intellectual biography of Ayn al-Qudat are varied but primarily geared towards a radical re-assessment of the terms of engagement with the medieval intellectual history of Islam and Iran. I am convinced that there is a serious need to de-mystify both the Islamic and Iranian intellectual histories via a critical assessment of the dominant modes of Orientalist historiography. In the introduction, I provide a detailed account of how I think this radical rethinking of the Orientalist legacy needs to be performed. Ayn al-Qudat’s life and creative imagination provide a unique opportunity to grasp the animating social and intellectual forces operative in the early part of the sixth/twelfth century in the western part of the Seljuq empire (reg. 429/1038-590/1194). It is impossible to grasp the relative significance of intellectual forces operative in this period unless they are released from the artificial hermetic seal under which they are customarily represented and thus made ready to be related to the dominant social and political forces of their time. While sketching the main features of Ayn al-Qudat’s creative concerns and animating ideas, I shall try to read some of the immediate material implications of his thoughts. As I shall demonstrate in the main body of this book, Ayn al-Qudat had some rather radical ideas about the nature of faith, the function of revelation, the purpose of divine messengership, and a range of related issues that collectively constitute the very creedal principles of Islam. He engaged these creedal principles in an inaugural and originary language, divorcing his narrative radically from the dominant mode of writing about such issues. I wish to demonstrate the precise nature of his radical narrative and outline the principal characteristics of his highly individualistic mode of engaging with the constitutional doctrines of a world religion. I commence my study of Ayn al-Qudat with an attempt to understand the dominant features of his social and intellectual circumstances. Ayn al- Qudat spent much of his adult life under the reign of Mughith al-Din Mahmud (reg. 511/1118-525/1131), a minor Seljuq prince whose higher aspirations were aborted by his more powerful uncle, Sultan Sanjar (reg. 511/1118-552/1157). The Sunni clerical establishment was highly influential under the reign of the newly converted Seljuqs, who were equally conscious of their relations of power to the continued legitimizing authority of the Abbasid caliphs. Philosophers and Sufis were equally present and relatively powerful in this period. Defending the Islamic lands against the invading Crusaders had given the Seljuqs a particularly powerful position vis-à-vis the Abbasid caliphs and in turn provided them with a free reign over the fate of their subjects. Ayn al-Qudat was actively present in the politics of his time and had close and friendly relations with a number of highly influential Seljuq officials.

(From the Preface to Truth and Narrative)

Columbia University

Columbia University Aljazeera

Aljazeera Middle East Eye

Middle East Eye Springer Palgrave

Springer Palgrave